London is pretty much full of people who weren’t born here, including me, and I’m interested in where they came from. Whenever I take an Uber, I usually try to engage the driver (who is almost always from overseas originally), in conversation and I like to something of their background. Most are economic migrants who have moved to London in search of either a better life in the UK or are working here to earn some money so that they can move back to where they come from with a relatively sizeable nest egg. All of them are living interesting lives.

My father’s family were economic migrants and I occasionally slip this fact into my conversations with the drivers. When they ask where my family came from and I tell them “Wales”, they shrug and smile as if that was not a proper migration. And maybe they are right in comparison to their own journeys. Its not that far geographically from the Welsh valleys to heart of London. Less than two hundred miles. My neighbour’s father walked it in search of work before settling down in a house off Nightingale Lane in Clapham. She still lives there and continues to wear a daffodil on St David’s Day and cheer for Wales against England in the rugby, failing Norman Tebbit’s “cricket test” with aplomb and often two fingers raised to the concept, the old rogue. Back in the 1930’s when her father walked to London and my grandparents moved east, and even more so before that in the nineteenth century when Taffs poured out of Wales in their tens of thousands and made London the second largest Welsh-populated city after Cardiff the distance traveled culturally was vast.

Leaving behind their language, their religion and their communities they replicated versions of these in the city when they arrived. Just like proper migrants.

One of the key parts of their culture was Chapel. Chapel was the building they worshiped in and it was also the name used to describe their non-conformist, often welsh-speaking, version of the Christian faith that they practiced. It discouraged alcohol and trips to the pub and usually offered a full social life to compensate. In London by the time of the outbreak of the second world war there were over thirty chapels in the city, each the centre of a strong Welsh community. This number has declined drastically. My Welsh neighbour keeps up many of her cultural connections with the old country but chapel is not one of them. She doesn’t go to church regularly any more but when she does, she finds it easier to pop into the local Church of England place. “Same god, isn’t it, love?” she explains. Only seven Welsh chapels remain including this splendid example in Eastcastle Street from 1889. There is talk in the Welsh community that further consolidation of the chapels may be needed and that, sadly, only one might ultimately be necessary. If so, my money is on this particular one being the last chapel standing. It was always a bit above the others. At least in its own mind. Prime Minister David Lloyd George was a member. It has recently been made over and looks splendid and shiny and as-new, particularly in the soft winter sunshine.

The most asked question about the building is what does “Capel Bedyddwyr Cymreig” that is written across the top of the chapel mean? The answer is Welsh (Cymreig) Chapel (Capel) in Central London (Bedyddwyr).

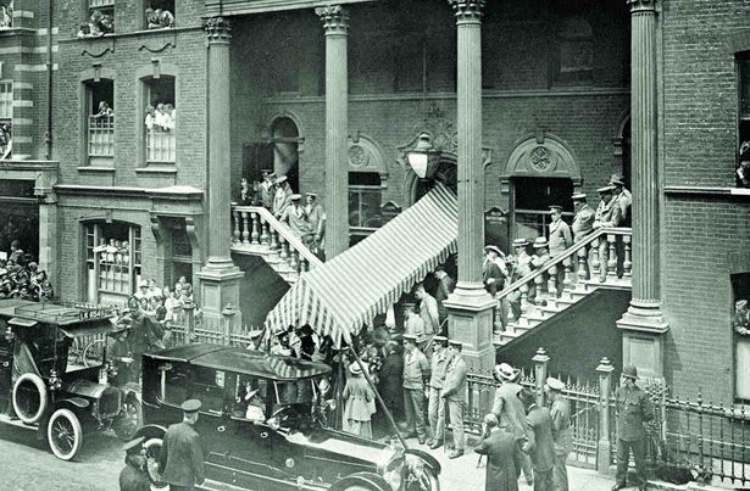

This picture shows the chapel on the day that David Lloyd George’s daughter was married in 1917. Incredibly there is some footage of people arriving at the wedding here. When I look at this I do wonder what happened to the millinery industry; everyone is wearing a hat. Sadly, no longer.