I went for a wander through old Chelsea yesterday, poking my nose into various nooks and crannies, taking photos and trying to imagine what Chelsea must have been like in the days when it was the home to many bohemian artists in the 19th and very early 20th centuries. Many houses have blue plaques commemorating former artist residents. Chelsea was a riverside village in those days originally cut off from London. Its still riverside but I don’t think many artists can afford to live there now.

Walking along Cheyne Walk from Chelsea Bridge, you come across a statue of James Abbott McNeil Whistler, the artist, on Cheyne Walk looking east along the Thames. He lived in a house on this street in the 1870’s. Following his gaze and walking past the house boats anchored off Chelsea Embankment, you arrive at an unimpressive patch of land called Cremorne Gardens. Knowing nothing of their history, I walked through them to get a better view of the Thames and discovered a mighty gate that had been one of the gates to the original Cremorne Gardens which stretched from the Thames to the Kings Road offering a similar selectio of entertainments, eateries, booze and spectacle as the more famous renowned Vauxhall Gardens in South London. These original gardens only lasted from 1845 until 1877, the land then being developed into the posh residential housing you can see there today.

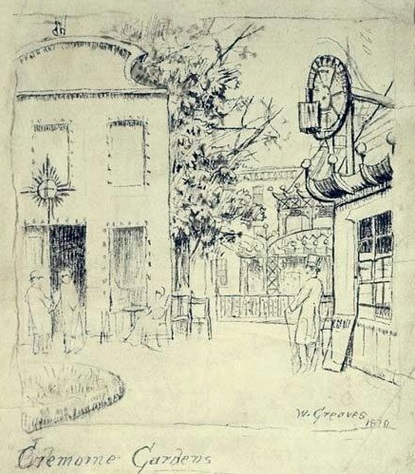

Whistler was a frequenter and fan of Cremorne Gardens. His admirer and assistant, Walter Greaves, who was a ferryman and used to ferry Whistler across the Thames (much as Greaves’ father had ferried Turner a generation before), before he began working for Whistler, sketched the artist in the Gardens in 1870.

Whistler himself painted a number of pictures set in Cremorne Gardens including Cremorne Gardens No 2, of 1877, which depicted the fashionable people who hung out in the Gardens and a series of Nocturnes, one of which Nocturne in Black and Gold: the Falling Rocket, of 1874, which became the source of a famous trial as the critic Ruskin derided it as “flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face” and not proper art and Whistler sued. He won the case but was awarded only a farthing in damages and the expenses of the trial helped tip him into bankruptcy.

Nowadays the scrap of land that calls itself Cremorne Gardens lacks the glamour or the footprint of its distinguished predecessor but it does have very pleasant views of the Thames and was completely empty on the day I visted except for a family walking off the Christmas pud.

There is one striking work of art in the gardens that is worth the visit alone. The London Fieldworks artist group have produced what they call Spontaneous City in the Tree of Heaven, which is a collection of bird nesting boxes arranged around a living tree, in the Gardens. I’m not sure whether Ruskin – or Whistler – would have considered it art, but I think it very lovely. The boxes are arranged so that the tree can continue to grow and expand beneath them.

James McNeill Whistler in the Cremorne Gardens, Chelsea by Walter Greaves

Cremorne Gardens No 2 by Whistler

Nocturne in Black and Gold: the Falling Rocket by Whistler: “flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face” ?